Unleashing the Leaders of Tomorrow: Discovering talent in the workplace

by Rianne Patel, Divisional Director, Asia Pacific, Gallagher Re

Introduction

Attracting talent is important but retaining and developing it is the real success of talent management.

This paper focuses on tapping into talent in the existing workforce; how to unlock talent potential rather than how to retain talent, although some factors may apply to both retention and development strategies.

Consider first, Maslow’s theory of human motivation, a hierarchy of needs based on motivational theory[1]. The theory suggests that if the lowest level of basic needs are unfulfilled, one would be motivated to attain them to some satisfactory degree before turning their attention towards fulfilling the next need in the pyramid.

The first four needs of the pyramid are referred to as deficiency needs by Maslow; if these needs are not being met, it can lead to negative physiological and psychological consequences[2]. Moving up through the pyramid, the motivation to achieve each need begins to move towards a desire for personal growth and achievement, rather than stemming from a lack of something. This is especially true for the highest level - self-actualisation – a key concept for unlocking talent.

The theory has met with criticism, however, for the suggestion that these needs are linearly related. Continually accumulating more inputs to address deficiency needs will not linearly increase satisfaction of one’s self esteem or potential for self-actualisation.[3] The order of needs is also arbitrary and people do not necessarily pursue or obtain these needs in this way.[4] In reality, the ranking of needs can vary by factors such as age and cultural upbringing, and priorities can change at specific times, such as when at war or in a recession.[5]

In my opinion, the theory can serve as a model for workplace motivations to provide a basic understanding of what drives employees, if not necessarily in the order illustrated by the Maslow pyramid in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs[6] The left side relates to the original theory, the right side is interpreted for the workplace.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, applied to the workforce.

Physiological needs – This block of the pyramid relate to basic needs of employment. For example, the need for a suitable salary and adequate workplace facilities.

Safety – The second block refers to where physical safety is prioritised and employee resources are protected. This can also include job security and emotional safety in the form of whistleblowing policies, sick pay, pension scheme benefits and so on.

Social needs & belonging – Here, the theory moves beyond tangible needs. This is where a sense of belonging and healthy relationships at work become important.

Esteem – This aspect of the theory considers how someone internalises their job successes; how they perceive their contributions to their job and how it is recognised and reinforced by the company. This is about the need to feel accomplished and so, an employee’s esteem can impact overall engagement with the business.

Self-actualisation – The pinnacle of the pyramid translates into maximising an individual’s potential. A person ultimately wants to feel that they are doing the best they can in their position, which keeps them motivated to continue their career path and grow into new roles. People need to feel suitably challenged and have opportunities presented to them in the form of training, responsibility, mentoring or promotions.

Generally, the first three needs are well-understood by organisations, easier to measure if they are being fulfilled and more straightforward to address. The upper levels of esteem and self-actualisation are more abstract and relate to the psyche. These are the areas that require attention to unlock talent and motivate employees beyond their current position.

This paper will focus specifically on what can block employees from reaching a more self-actualised state and how an organisation can remove those barriers. There are three sections that will explore examples of these barriers, from the perspective of the individual, manager, and the organisation.

The Individual

The uniqueness of each individual employee is the beauty of the workplace, providing it with diversity of thought, background and general perspective. However, this means there is no one-size-fits-all approach to addressing a person’s needs and motivations, which does mean that at the individual level, people need to be understood properly.

Highly engaged employees are three times more likely to say that they feel heard at their workplace[7]. Managers, or the business more widely, should aspire to understand employee’s personal circumstances and backgrounds, within reason, and career aspirations and expectations. Knowing what motivates them and whether their needs are being met is key to knowing how to take action to support them and improve their engagement with the business.

Barrier example 1: Imposter Syndrome

Mental health issues are sadly something that many people experience in their lifetime, either temporarily or long-term, for any number of reasons. Many industries have put a spotlight on this topic and made it less of a taboo subject but for many individuals, it can still be a deeply personal issue.

In this section, we will focus on one particular struggle: imposter syndrome. Imposter syndrome is essentially where someone has consistent feelings of doubt in their abilities and feels like a fraud, despite evidence of their success.[8] Characteristics can include:

- Not internalising successes or putting successes down to luck

- Lack of self-confidence

- Perfectionism and having unrealistically high standards can perpetuate imposter syndrome

- Fear of failure or fear of being ‘found out’ can lead to avoidance, turning down opportunities or not speaking up with ideas, for example.

- Procrastination or paralysis – relating to the ‘flight’ response in the term ‘fight or flight’; freezing up when triggered or putting off things, which then builds feelings of overwhelm[9]

Imposter syndrome can lead to a person having anxiety or burnout.[10] Naturally, employees cannot perform at their best if they are suffering with mental health issues, of any kind.

A key point to note here is that organisations will most likely be trying to unlock potential talent in someone who has imposter syndrome, as it commonly presents in high achievers. Clance & Imes (1978) initially defined it to be an occurring phenomenon in high achieving women[11], but more recent research has shown that men are just as susceptible to it.[12] There are, however, differences in the way that imposter syndrome is experienced by men and women. For example, as men become more senior, the likelihood of imposter syndrome affecting performance goes down significantly. This is the opposite for women, as they become more senior[13]. For women, becoming more senior could be more isolating; as at August 2022, the Insurance Age revealed that women held only 15.7% of senior management roles in the broking sector[14]. Feelings of being an outsider can drive imposter feelings.[15] For the same reason, minority groups are at much higher risk of developing imposter syndrome.

Imposter syndrome is where people are not able to believe that they are capable and have earned their place, rather than being about incapability itself. To support people who suffer with this, organisations could consider the following:

- Cultural improvement where there is a stigma around mental health. Organisations should continue to work towards highlighting the importance of mental health and promote discussions around wellbeing[16]. Other cultural factors to assess would be whether there is, for example, a culture of working long hours and weekends, or having an overly pressurised environment. Culture is discussed later in this paper.

- Focus on the diversity and inclusion agenda to validate people in the workplace. This includes addressing issues such as the gender pay gap, gender and racial gap in management positions and lack of diversity in hiring.

- Feedback mechanisms, such as goal setting and performance reviews are important, to measure progress and highlight successes. This point also applies to employees being able to feedback on the company and share their thoughts on what needs to change for their wellbeing to improve.

- Have a mental health strategy[17] that includes providing access to mental health support or therapy, or providing mentors or peers who are prepared to talk about wellness and support each other. Training managers to better spot and manage a deterioration in their employees’ mental health should also form part of this strategy.

Barrier example 2: Inflexibility

We cannot disregard the fact that some people may not want to reach their full potential. Work-life balance is one of many factors considered by people when deciding their career paths, particularly when considering how high they want to climb up the career ladder. Typically, this is because seniority comes with a worse work-life balance or inability to switch off from work[18].

We cannot disregard the fact that some people may not want to reach their full potential. Work-life balance is one of many factors considered by people when deciding their career paths, particularly when considering how high they want to climb up the career ladder. Typically, this is because seniority comes with a worse work-life balance or inability to switch off from work[18].

The chaos and uncertainty of the pandemic led to people rethinking their careers and re-evaluating personal aspects of life. This led to a phenomenon described as The Great Resignation, where job resignations were happening with unprecedented frequency. People are now looking at work and the role they want it to play in their lives in a different way and switching to jobs that better align with their new values.[19]

A newfound importance has been placed on being able to work flexibly. This relates to those who want to reach their potential but personal circumstances, or simply preference to work differently, may not allow them to in their current working role. Organisations need to provide the option to work from home for some or all days, where possible. Flexibility can also be provided in the hours that people work, whether that be that they are different to the standard, or they are condensed, for example.

It has been suggested that employees will be more motivated and committed to their work where they feel supported and trusted to work flexibly.[20] Other benefits of flexible working include:

- Retaining employees who may not be able to work full-time in the office.

- Addressing skills gaps and being able to attract top talent from a larger pool of people, as there are no geographical restraints.

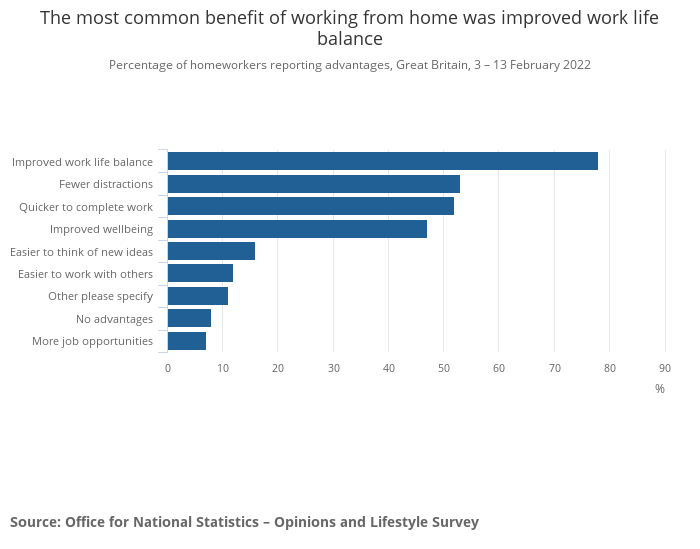

- Reducing sickness absence by boosting a healthier work-life balance. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) conducted a survey in May 2022 and found that 47% of participants reported improved wellbeing with hybrid working.[21]

- Improved productivity[22]. The ONS survey also found that 53% of participants reported fewer distractions working from home and 52% found they completed work faster.

Figure 2: Office for National Statistics – Opinions and Lifestyle Survey Results[23]

It is important that organisations and managers allow for their workers to have this flexibility without fear of repercussions. This would include ensuring that women’s careers are not more adversely impacted than men when opting to work flexibly, as one study by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) has found[24].

The CIPD study further suggested that some homeworkers may also be overworking, particularly managerial and professional workers, as there are more blurred boundaries between work and personal life. Therefore, although flexible working can benefit both employees and the business, it should be managed appropriately.

Equally, at the other end of the spectrum, there may be people searching for a higher degree of in-person commitment. They may have disliked the isolation of working from home during the pandemic or are simply in the proportion of people who feel that they work better from the office. Organisations therefore also need to consider and cater to those who do not want hybrid working.

The Manager

Managers are responsible for achieving the goals and objectives of a company through the management of resources.[25] A major component of this resource is human; managers need to ensure the right people are hired, the team works efficiently to achieve overall objectives and take an interest in the growth of individuals.

The most obvious barrier to unlocking talent relating to managers would be those managers who are simply not what their employees need. Two in five employees have quit because of a bad manager[26]. What constitutes as a ‘bad’ manager does depend on individual opinion and experience, but it would drive top talent out of the business and certainly not bring out the best in whoever is left behind. However, this section does not directly discuss the quality of managers. The barriers discussed below are slightly more obscure or indirect barriers to unlocking talents in the team, from a managerial level perspective.

Barrier example 3: High performance does not equal high potential

High performance looks at past performance but high potential needs assessing based on potential future contributions.

There is a ceiling in every role for as long as the role duties are the same – unlocking talent is about knowing who can progress into new roles, especially leadership roles. Research published by the Harvard Business Review shows that more than 70% of today’s top performers lack critical attributes essential to their success in future roles.[27] Three critical attributes that were found to really matter when choosing a future leader:

- Ability – there is a need to have the expertise and intellect to handle business. This also extends to emotional intelligence, which is partly defined as the ability to recognise and influence the emotions of those around you.[28]

- Engagement – having some level of personal connection and commitment towards the company and its mission. This would therefore be impacted by any current job dissatisfaction.

- Aspiration – not everybody will want to maximise their potential. It is important to know how fast or how high someone is willing to climb a career ladder, as people need to be committed to leadership roles.

The barrier here is that managers may be earmarking the wrong candidates for leadership roles or other work opportunities, and the associated investment into these people will therefore be misplaced. There are aptitude tests and other assessments that can be undertaken to flag high potential talent versus high performance talent. However, an awareness of this key difference is the main takeaway here, as managers can then direct, or redirect, their efforts to the right people.

There needs to be a mechanism of feedback on individuals to assess them properly and flag them as high potential employees. Most organisations have annual performance reviews in place, but these should be developed to ensure they are properly conducted and focus on more than just past performance. For example, they could comment on how engaged the individual is with the business and what their career aspirations are.

The next step after identifying high potential would be to foster development, which is discussed later in this paper.

Barrier example 4: Bad hires

Unlocking talent in a low performing individual is not what this section is referring to. This barrier is in relation to the team that this would affect.

Recruitment is not always successful; it can be hard to know for certain how someone works or will fit into a team without trialling them on the job. Not only is it demotivating for the wider team to work alongside poor hires, but it can be very inefficient[29], as they may also have to spend time and energy in making up for this person. It can mean that they must either do the parts of the job that the new hire is incapable of doing, or they spend additional time correcting work. In worst cases, there could be a loss of business if the team is unable to manage this increased workload, which could affect their level of service to clients, for example.

If team members with potential talent are sidetracked in this way, they may not have the capacity to apply themselves to other opportunities or more challenging things; their growth potential may be stunted or slowed down. Equally, team managers can become preoccupied with this hire, as they may require a lot more attention, which again is to the detriment of the wider team who could be left feeling less supported.

Monetarily, a poor hire is costly; from the money spent on recruiting them to the money allocated to their salary[30]. Depending on how money is budgeted for within individual teams, this will mean less budget for other hires, for training and development and for promotions or salary increases to expectant employees, all of which can impact motivation.

Equally, if the individual is a poor fit socially, a team that may have been content before, may now feel awkward or unhappy as the mood has changed. Not being able to enjoy the company of teammates can be demotivating. Therefore, an individual could be further away from self-actualisation in the workplace if they are severely struggling to satisfy social needs to feel connected and have good working relationships.

One consideration to overcome an inadequate hire, would be to make proper use of probation periods, either by extending them where necessary or dismissing an employee during this period. It can be more difficult or time-consuming to terminate someone’s employment if it goes beyond this period, depending on employment law in the country of employment. In the UK, the dismissal must be for a fair reason and the dismissal process must be fairly undertaken[31].

Probation periods are generally a good tool to ensure both the employee and employer see each other as a good fit. They should include gathering team feedback, regular reviews with the worker and where necessary, managers should have meetings with Human Resources (HR). HR will have experience in dealing with reservations around a new hire and should be able to assist managers in assessing the way forward with the worker, or whether termination of employment is the optimal solution. These reviews are also an opportunity for the new hire to reflect and feedback on their experience to date.

Other solutions to avoid the potential for poor hiring would include having proper hiring practices, such as hiring from a wider pool of people and fair application processes. Clearly marketing job duties and expectations will not only attract the most appropriate applicants but also reinforce to hiring managers what they are looking for specifically, ensuring that the right questions are asked during the hiring process.

The Organisation

Ultimately, it is up to the company to have a talent management strategy and to create a positive employee experience and environment. A talent management strategy will need to closely align with business objectives, so that talent is recruited, developed and retained with these objectives in mind. Without an appropriate strategy, a company may be distracted from achieving core objectives if handling talent retention issues or other employee-related concerns on a regular basis.

Barrier example 5: Company culture

A familiar term in the workplace, company culture can shape the brand and reputation of an organisation and can impact its ability to attract and retain top talent. It can be defined with a set of ideas, values and policies but does not actually come to life until the workforce embodies them, and it becomes a living, breathing thing. The relationship between culture and the workforce is almost reciprocal in this sense; while company culture shapes employee behaviour, employee behaviour also influences and shapes the company culture.[32]

Good company culture can strengthen an organisation’s overall success, reduce risk of misconduct, and protect and enhance the company reputation and brand.[33] Poor, or even toxic, company culture is a barrier to unlocking talent as it directly impacts retention of talent and can lead to a lack of productivity and motivation.[34] Many employees will be unhappy, and their commitment to and engagement with the business will be impacted, making it harder to spot and nurture top talent.

Poor culture can be linked to tardiness or absenteeism of employees, or by their overworking. The ‘always on’ culture, referring to the expectation that employees are always available and responsive to work demands outside of work hours[35], has become more apparent with the merging of work and homelife during the pandemic. Aviva conducted research to assess the prevalence of this culture and found 44% of people feel like they never fully switch off from work.[36] This can directly impact employee wellbeing and may increase chances of burnout, something that high potential talent is not immune from.

There may be substantial gossip in the workplace or unhealthy levels of employee competition. The organisation could be a hostile workplace, with high instances of bullying or harassment. This was a major concern for the insurance industry in London in 2019 when various cases of bullying and harassment had surfaced in the media and highlighted the lack of whistleblowing policies in place for staff to speak up and report issues internally.[37]

Culture is a broad and all-encompassing term, and cultural fixes will need to be embedded at all levels of an organisation. A change in culture must be high priority for the highest levels of management[38], who also need to lead by example. The business must first understand what the current culture is and closely examine what existing ideas, values and behaviours allowed bad practices to develop, in order to correct them and reinforce values that align with the desired culture. Culture and cultural change therefore need to be measured and captured.

KPMG have identified a link between culture and accountability, whereby cultural norms and practices of a company can greatly influence the level of accountability that is expected, accepted and enforced.[39] They determine that cultures of high trust and transparency tend to have greater emphasis on accountability, and employees will hold themselves accountable for their actions as they believe in the importance of integrity and honesty. Cultural attitudes towards consequences and enforcement also play a role in accountability and having clear protocols in place to address instances of misconduct or non-compliance would incite employees to conduct themselves with care. These findings tie into the idea mentioned previously that employees and culture have a reciprocal relationship; one impacts the other.

Barrier example 6: Talent management is not the same as talent development

Talent management is a high-level strategy of recruitment and retention to ensure organisational needs and targets can be achieved. Talent development is closely related to this but puts emphasis on positioning existing employees for career advancement in a way that aligns with the company's mission[40]. The latter is more specific and personalised to employees.

Talent management is a high-level strategy of recruitment and retention to ensure organisational needs and targets can be achieved. Talent development is closely related to this but puts emphasis on positioning existing employees for career advancement in a way that aligns with the company's mission[40]. The latter is more specific and personalised to employees.

The goal of talent development is to create a place where people are engaged, have high work performance, and are constantly learning and growing.[41] It is therefore directly linked to unlocking talent potential.

Talent development can lead to better retention and engagement, as employees feel invested in and supported by the business. With proper training and challenge in their roles, they can develop themselves to fill skills gaps and become better innovators, leading to increase efficiency and productivity in the workforce. Upskilling existing talent and investing in employee development also allows for succession planning within the business, especially in relation to preparing high potential talent for promotions and career growth.

Figure 3: Academy to Innovate HR - Talent Development Goals[42]

Having a talent development strategy is important to achieving these goals. An organisation can start by having a dedicated function for talent development, to design and develop an effective and appropriate programme that align with the company’s objectives and overall mission. Knowing what this programme needs to entail will mean identifying skills that need developing at different levels of staff and assessing the best formats to deliver this training.

The organisation can also make provisions for supporting and developing employees who want to change or adapt their roles, which may involve supporting further education or providing rotational opportunities and secondments, for example. These ideas can allow employees to engage more deeply with other functions in the business and would likely assist with retention of talent.

Conclusion

In my opinion, and in agreement with the workplace interpretation of Maslow’s theory, employee wellbeing and motivation are key considerations for unlocking talent. When a person is generally in a good place, comfortable in their routine and work environment, and has the mental capacity and resources to push themselves, they will be more motivated and capable of achieving greater things.

Unlike the implied order of needs in Maslow’s pyramid, I believe that the process of unlocking talent in each individual is less of a stepped approach and more like a situation of keeping all the plates spinning. There are many motivational components and workplace considerations to note when developing talent, in addition to the six illustrative examples discussed in this paper. However, at any one time, these components will be satisfied to varying degrees for each employee and the weight of importance on each will be different as well.

Responsibility for employees reaching self-actualisation and reaching their workplace potential partly lies with themselves, to take a proactive approach to their career and align themselves with their preferred roles and experiences.

The responsibility also lies with managers, who must support their employees to build the careers that they want and provide necessary opportunities for talent to grow. Potential talent does have to be spotted and nurtured in some people, and it is important for the manager to notice this.

The organisation is also responsible for creating the environment to unlock the collaborative potential of talent and provide resources necessary for their well-being and progression. The organisation needs to provide managers with the tools they need to effectively unlock and manage talent within their teams too.

Humans are complex beings with unique needs, wants and motivations. In this regard, given that there is no blanket solution to unlocking talent in everyone, it can take a more personal approach and an investment as simple as time, to get to know your employees and understand what makes them tick.

[1] Maslow, A. H. (1943), A theory of human motivation.

[2] McLeod, S. (2016), ‘Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs’ <https://www.craigbarlow.co.uk>

[3] Fieldman, A. (2020), ‘The Problem With Maslow’s Pyramid’ <https://medium.com>

[4] Medical News Today (2022), ‘Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, uses and criticisms’ <https://www.medicalnewstoday.com>

[5] King-Hill, S. (2015), ‘Critical analysis of Maslow's hierarchy of need’. The STeP Journal Student Teacher Perspectives.

[6] Sodexo Engage, ‘Applying Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory to HR Responsibilities’ <https://www.sodexoengage.com>

[7] Ceniza-Levine, C. (2021), ‘New Survey Shows The Business Benefit of Feeling Heard – 5 Ways to Build Inclusive Teams’, Forbes <https://www.forbes.com>

[8] National Library of Medicine (2021), ‘How Feeling Like an Imposter Can Impede Your Success’ <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov>

[9] Josa, C. (2022), ‘The 4 Ps of Imposter Syndrome’ <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0o-lwOdF8GI&t=9s>

[10] Josa, C. (2019), ‘How Is Imposter Syndrome Affecting Businesses?’ [White paper]

[11] Clance, P.R., & Imes, S.A. (1978), ‘The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention’ <https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1979-26502-001>

[12] Josa, C. (2019), ‘How Is Imposter Syndrome Affecting Businesses?’ [White paper]

[13] Josa, C. (2019), ‘How Is Imposter Syndrome Affecting Businesses?’ [White paper]

[14] Kenning, E. (2023), ‘In conversation: Broker Diversity Push’, Insurance Age <https://www.insuranceage.co.uk>

[15] Young, V. (2011), ‘The Secret Thoughts of Successful Women’, New York, Crown Business

[16] Mind Charity, ‘How to promote wellbeing and tackle the causes of work-related mental health problems’, <https://www.mind.org.uk/work>

[17] Mind Charity, ‘How to promote wellbeing and tackle the causes of work-related mental health problems’, <https://www.mind.org.uk/work>

[18] Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2019), ‘UK Working Lives – The CIPD Job Quality Index’, <https://www.cipd.org>

[19] Morgan, K. (2021), ‘The Great Resignation: How employers drove workers to quit’, BBC Worklife <https://www.bbc.com/worklife>

[20] Brown, J. (2021), ‘Flexible working makes employees feel more trusted, poll finds’, CIPD – People Management Magazine <https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk>

[21] Office for National Statistics (2022), “Is hybrid working here to stay?’ <https://www.ons.gov.uk>

[22] Half, R. (2022), ‘5 Benefits of flexible working for your employees’ <https://www.roberthalf.co.uk>

[23] Office for National Statistics (2022), “Is hybrid working here to stay?’ <https://www.ons.gov.uk>

[24] Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2019), ‘UK Working Lives – The CIPD Job Quality Index’, <https://www.cipd.org/uk>

[25] Study Smarter <https://www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/business-studies/managers/#:~:text=Managers%20are%20responsible%20for%20achieving,%2C%20making%20decisions%2C%20and%20reviewing.>

[26] Urquhart, J. (2022), ‘Two in five employees have quit because of a bad manager, study finds’, CIPD – People Management Magazine <https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk>

[27] Martin, J and Schmidt, C. (2010), ‘How to keep your top talent’, Harvard Business Review <https://hbr.org>

[28] Landry, L. (2019), ‘Why Emotional Intelligence Is Important in Leadership’, Harvard Business School Online – Business Insights Blog <https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/emotional-intelligence-in-leadership>

[29] Half, R. (2022), ‘3 serious consequences of a bad hire’, <https://www.roberthalf.co.uk>

[30] Half, R. (2022), ‘3 serious consequences of a bad hire’, <https://www.roberthalf.co.uk>

[31] Gov.UK, ‘Dismissing staff: Dismissals for conduct or performance reasons’ <www.gov.uk)>

[32] Hppy, ‘The impact of company culture on talent management’ <https://gethppy.com/talent-management/company-culture-in-talent-management>

[33] KPMG (2023), ‘Championing accountability through organisational culture’ <https://kpmg.com/ie/en/home/insights>

[34] Hall, J. (2020), ‘Company Culture Doesn’t Just Impact Well-Being — It Also Impacts Productivity’, Forbes <https://www.forbes.com>

[35] Jamaludeen, J. (2021), What is ‘always-on’ culture?’, <https://jafferjamal.medium.com>

[36] Aviva (2020), ‘Employees struggle with ‘always on’ culture’ <https://www.aviva.com/newsroom/news-releases>

[37] Sweeney, A. (2019), ‘Making Impactful Change’ [Speech given at Insurance Insider Progress Network Event], Bank of England < https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech>

[38] Kaplan, M., Dollar B., Van Durme, Y. et al., ‘Shape Culture, Drive Strategy’, Deloitte Insights <https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights>

[39] KPMG (2023), ‘Championing accountability through organisational culture’ <https://kpmg.com/ie/en/home/insights>

[40] Sokolowsky, J. (2023), ‘What is talent development and why does it matter?’, Chronus <https://chronus.com>

[41] The Highlands Company (Blog), ‘Talent Development vs. Talent Management’, <https://www.highlandsco.com/talent-development-vs-talent-management/>

[42] Taylor, T.C., ‘Talent Development: 8 Best Practices for Your Organisation’, <https://www.aihr.com/blog/talent-development/>